In Lama Passage passing the Columbia, the Alaska ferry

2-3 August 2012 Pruth Bay, Fitz Hugh Sound

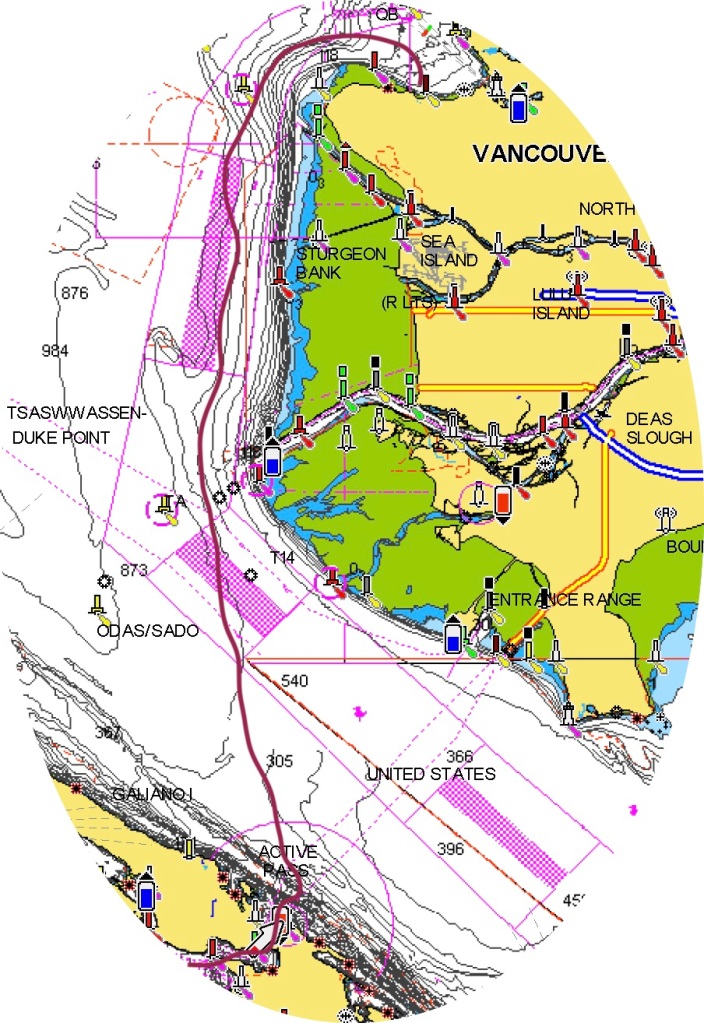

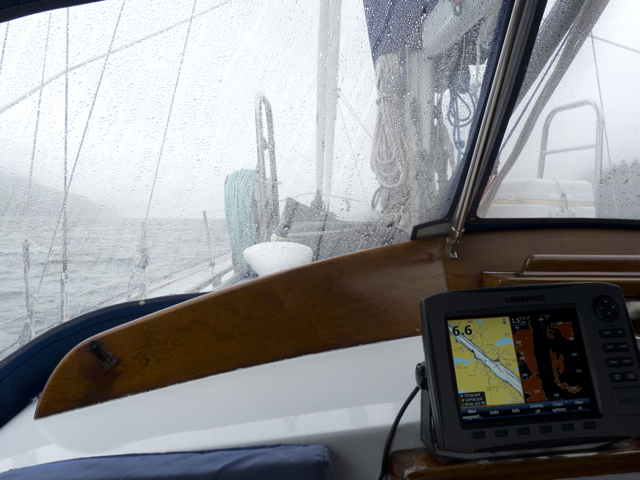

We met our friends, the young kayakers from Juneau again, on a rainy day in the laundromat in Shearwater. They too had stopped here to clean up and reprovision. Finally, clean sheets, fresh fruits and vegetables, dry socks! We packed the boat with groceries, (Karin had been baking so much bread that we needed more flour,) and topped up on fuel and water. Time to head out, down the Lama Passage again, to Fisher Channel, and then Fitz Hugh Sound. We saw the kayakers one last time, flung out across a steep beach along Lama Passage.

Alaska kayakers on the beach

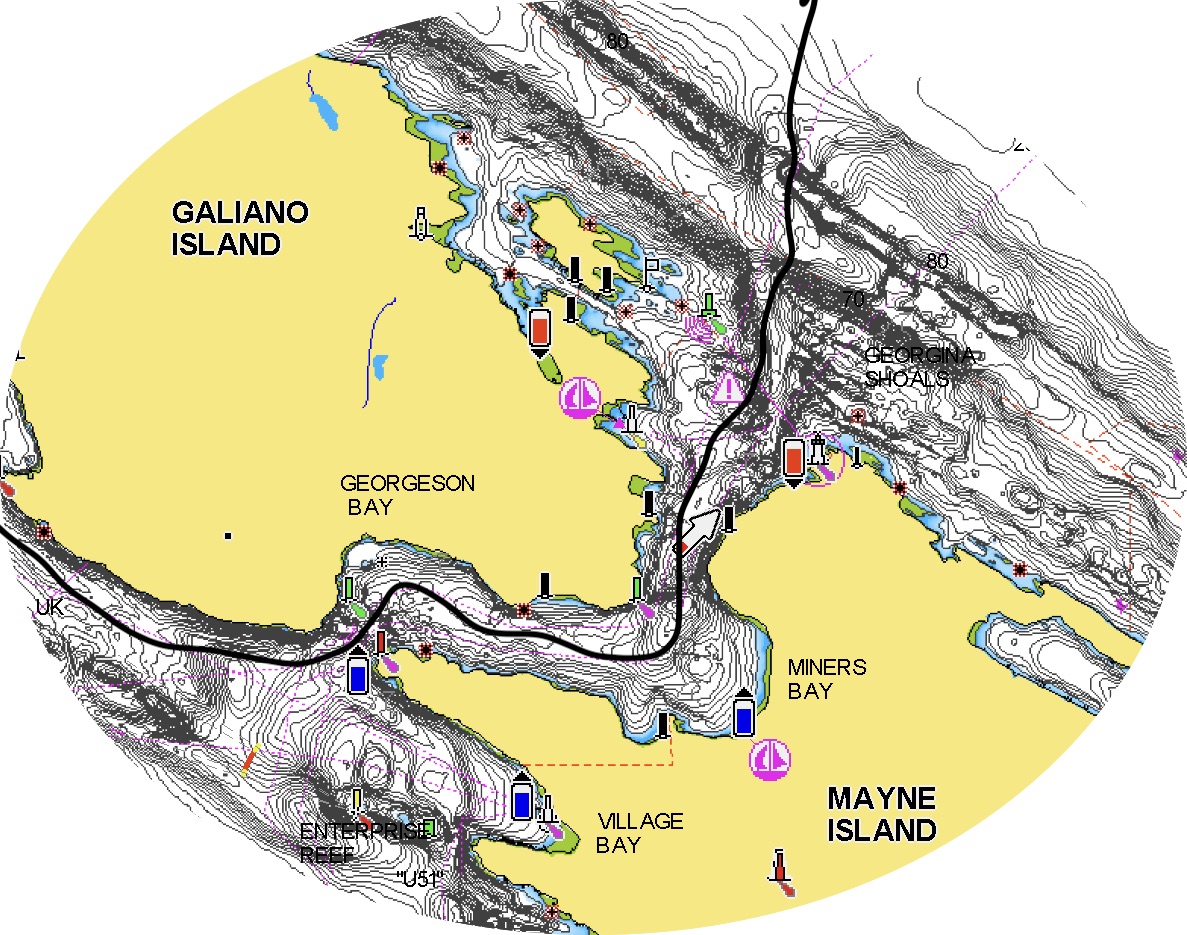

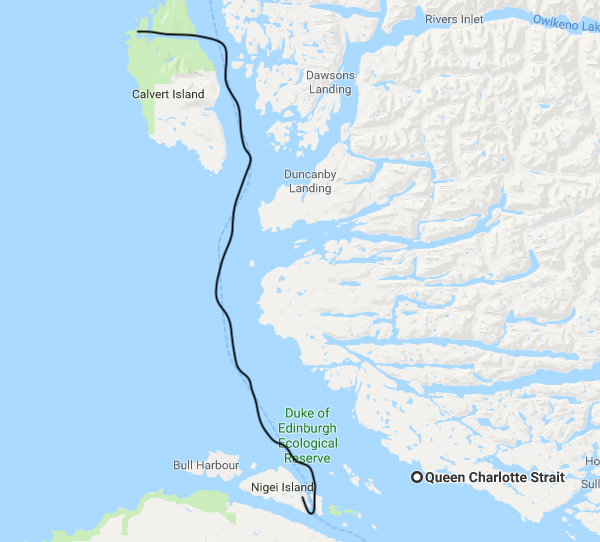

Blue skies and a perfect breeze. We reached speedily down Fitz Hugh Sound, then seven miles up the narrow Kwakshua Channel that cuts deep into Calvert Island, into Pruth Bay. As we entered the channel we saw many vessels trolling for salmon. The fishing was supposed to be good, but it didn’t look as if anyone was catching much.

Quoddy”s Run on the Central Coast

Still, it was a beautiful sunny afternoon. Around us, low cliffs. We had entered a glacier-carved channel where scrappy windblown spruces clung to crevasses in the steep rock walls, and erratics dotted the heights, as if placed there by giants. It looks like Nova Scotia! Marike said as we motored into Pruth Bay after taking down the sails. Indeed it did.

Hakai Beach rocks

We dropped our anchor, lowered our dinghy into the water and paddled towards shore.

A low tombolo separated open sea from Pruth Bay and Kwakshua Channel; on that bit of earth sat a large red-roofed lodge and a series of dwellings, once part of a fishing lodge, but now the site of an unusual undertaking called the Hakai Beach Institute. Impressive docks fronted the place; moored there were two red-trimmed aluminum motor vessels with closed passenger cabins, the Hakai Express and the Hakai Spirit, both clearly capable of high speeds in rough weather, along with a series of smaller vessels. We noticed, as we paddled around the docks, finally tying up where a sign indicated that we might, that all of the services one might wish at a dock–water, electricity, and fuel–were run along the dock in closed pipes; it was the tidiest, sturdiest bit of dockworks we’d ever seen. Signs on the walls of a little gatehouse on the dock greeted visitors and explained how they might access wifi services. We’d heard from other sailors that free wifi was available here, but by this time, we’d lived so long without the internet that we thought it could continue to wait.

Hakai Beach Institute lodge

We walked up the ramp to land, where signs suggested we should enter and sign in at a small house with a notebook, sign in sheets and a computer. We signed in, and then studied the map for the route to the beach. Along the way, we walked through well-kept gardens, past the red-roofed lodge and several stand-alone houses, across a bridge and into the trees, then through a clearing filled with several yurts containing beds and tables and chairs. The trail wound through tall grasses and bushes and silver snags here and there, and into the trees again—Sitka Spruce, regrowing after these shores had been scoured of the trees by the aircraft industry during the course of World War II (think the Spruce Goose). Then there was the beach, glowing in the late afternoon.

Eagle with silver snag

A long sandy spit at low tide. The sun slowly lowering in the west over many jagged islets. Birds wading in the shallows, kelp strewn across the beach. Numerous steep rocky outcrops, like those we’d seen at Los Frailes, in Mexico, where the surf had first knocked us down and rolled our dinghy, years ago. In the cracks at the base of these rocks was a riot of colour–purple and orange sea stars twisted together, and green aggregating anemones eating crabs. Ospreys circled overhead, while an eagle watched us from her perch in the top of a tree on the top of one of the steepest stony outcrops.

Kelp on Hakai Beach

We were in a stunning and clearly sacred place.

Birds wading in the shallows

Before we returned to our boat, we made an appointment to come back the next morning and interview the founders and owners of the Institute, Eric Peterson and Christina Munck. Eric invited us to the lodge for breakfast and lunch while we talked with him. We met in the first floor of a vast two-storey hall decorated with First Nations and local artists’ works and equipped with a kitchen that served tens of thousands of healthy, gourmet meals each year. The food was indeed delicious, the abundant fresh fruits and greens a welcome sight to long-distance sailors.

Sun star on the beach

Peterson and Munck had backgrounds in healthcare, specifically diagnositic imaging, and botany, and they were interested in environmental management and land conservation. They had become passionate about how best to deliver health care in poorer countries, where, as Peterson said, “all of the equipment and supplies in the world won’t do any good if you don’t have competent people in place.” They started a family organization they called the Tula Foundation; its first aim was to enable the delivery of primary nursing care in key communities in Guatemala.

Sea star with aggregating anenome

Meanwhile, Munck had started to work on the Central Coast with the Nature Conservancy. Her interest had been in securing land that had been abused industrially, but that had high enough “ecological attributes” that it might be recovered and made usable again. She had gotten involved in sorting out what to do in Rivers Inlet during the collapse of the wild salmon stocks. Rivers Inlet had had the third largest salmon runs, after the Skeena and Fraser Rivers, but it was the first large salmon fishery in BC to collapse. This devastated the Oweekeno First Nation, now a fishing people without fish or boats. During the course of conversations about what sort of science or new undertakings might happen in the wake of the collapse of the fishery, one elder remarked to Munck and Peterson that his community was in need of primary nursing care too. Suddenly it began to seem as if all of their interests—in science, healthcare delivery, and ecological recovery—might be converging. They began to look for a base around Rivers Inlet, an old fishing lodge perhaps.

kelp fan

Indeed, Munck had once visited Hakai while it was still a fishing lodge for a conference, and was stranded there by bad weather. She fell in love with the place, with its access to the protected waters of the inside passage, as well as the open sea, and with its mix of wilderness (wolves on the beach!) and a history of human uses, including its status as traditional territory and an important sacred place to the Oweekeno and Heiltsuk First Nations. When the lodge was put up for sale in late August 2009, she and Peterson bought it, and began to establish the Hakai Beach Institute. “We are stewards of this place,” Peterson told us. “We don’t really own it. We provide a neutral meeting ground for members of the four First Nations of the Central Coast (Oweekeno, Heiltsuk, Nuxalk and Kitasoo/Xai Xai); we use our boats to bring people together to meetings.”

We recalled seeing one of the Institute’s boats speeding through the southern end of the Grenville Channel. When we mentioned that, Peterson said, yes, that was some elders from Hartley Bay we’d picked up.

sea stars dancing

Since 2009, the mandate of the Institute has expanded so that it brings together members of the First Nations, university researchers, government agencies, and the Coast Guard. The place thus engages teaching and research in a variety of areas from scientific monitoring of climate change and marine fauna, to archeology, the earth sciences, and the arts. As a stewardship zone, the Hakai Beach Institute has provided a neutral, casual meeting place for First Nations people from communities in Bella Bella, Bella Coola, Klemtu, Rivers Inlet and Hartley Bay to get together to strategize around key issues such as the Northern Gateway Pipeline, or how to further protect important species such as the Spirit Bear. According to Peterson, traditional enemies sometimes find that a casual encounter at Hakai with good food, trails, beaches, and facilitation, can lead to reconciliation and agreement on some key issues. Hakai has provided leadership training for First Nations youths, and has begun to expand the network of Coastal Guardian Watchmen begun in Haida Gwaii. Hakai also collaborates with Parks BC in order to carry out basic science and monitoring and to build trails and boardwalks along the ocean side of Calvert Island.

Coastal Guardian Watchmen Network

Peterson was especially proud of the physical plant of his Institute. He described himself as a “city manager,” and gave us a tour of the waste and electricity systems of this off-the-grid ecological village which employs 20 staff members on each rotation, as well as housing its owners, visiting scientists, and others. Hakai is an experiment in green technology and recycling: even the grease from the kitchen is disposed of through microbial grease eaters, and then becomes compost for the gardens. The electricity plant is increasingly solar, taking over from generators. Power is stored in huge battery banks, and a state of the art water purification system is set to go online this year.

We enjoyed our conversation with Eric Peterson; perhaps most of all, we were engaged by his musings about how the Central Coast was not a pure wilderness, but rather bore the traces of a time when the area was more densely populated. The land had been greatly culturally modified over centuries, not just by now defunct freeholder fishing, or hand logging, and mining industries, but far earlier by First Nations clam farms, as evidenced by middens, and forest cultivation.

Sea stars, aggregating anenomes, crab bits

We were struck by the resonances between our observations, what Peterson had been saying and what we had been reading in a book entitled the Last Great Sea by Terry Glavin. There Glavin marshals an abundance of archeological evidence to suggest that, contrary to what many of us have been taught, the First Nations of the North Pacific rim were never nomadic hunter gatherers who, on some date after the last ice age, marched across the Bering Strait and then spread across the Americas. Rather, the specific character of Pacific coasts and various Pacific First Nations communities from Japan and the Koreas to Alaska and British Columbia, suggest that coastal dwellers have been mariners, and seasonal farmers of both sea and land for the last 9000 to 12,000 years. There is evidence of clam farming, permanent settlements around these clam beds, habitations, art works, and short migration routes along the coasts and islands following salmon and oolichan runs, and other seasonal foods. There is also quite a lot of archeological evidence of trading between these First Nations and others, both to the West and in the North. Salmon fishing technology more than 9000 years old—a small grooved stone sinker for a salmon line–was found in Namu, on the Central Coast, “the oldest known piece of fishing gear in British Columbia….” Glavin says (32). Beneath that find was more human detritus. As Glavin reports, “The antiquity of the site established Namu as one of the first fishing villages anywhere on earth” (33).

sunset on Hakai Beach

Human cultures in the North Pacific were shaped not only by the sea, Glavin argues, but, overwhelmingly, as even the landscape itself was, by salmon. The abundance of the salmon made for bountiful, massive forests and human societies of great richness and development:

“North Pacific cultures were composed of self-sustaining, densely populated societies marked by rigid hierarchy and social rank, based in large, permanent winter villages. And nowhere else on earth were human societies so fully integrated within marine ecosystems. Nowhere else were people so dependent upon fish. Among some North Pacific cultures, the isotopic signature found in human remains is exactly the same as that found in dolphins.

“The next thing you see is salmon.

“From the very beginnings of human history in the North Pacific, salmon were involved. Salmon were there at the close of the last ice age, and for most of history since then, salmon—not human beings-were the species most responsible for altering the shape and form of the continents around the North Pacific….Every year, millions of tonnes of energy was brought up out of the depths of the North Pacific and deposited deep within the continents surrounding it…” (Glavin 9-10).

In fact, as we had been sailing along this coast, the three of us had read a number of other books loaned to us by Dawn Burkmar, part of her now two-year project to educate us about the land and history of her beloved British Columbia. Most of them pointed to a much more crowded, inhabited coastline than the one we found. Here, as in Nova Scotia, the coming of white settlers had destroyed First Nations health and communities. Then increasing mechanization, urbanization and the arrival of huge commercial fishing and logging operations diminished and destroyed the white settlements scattered along the coast, leaving behind ghost towns, rusting ruins and timber that rotted and returned to the forest.

Books from Dawn’s BC library

We read Up Coast Summers, by Beth Hill, which compiled the journals and photographs of Francis Barrow, and described summer voyages in the 1930s and early ‘40s from the Gulf Islands to the Broughton by Francis and Amy Barrow, amateur archeologists. They were constantly stopping off in various communities to visit with settlers along the coast or making detours for social gatherings. Three’s A Crew, by Kathrene Pinkerton, described cruising the coasts of British Columbia and Alaska in the 1920s and 1930s. We were struck by how many people living along these coasts were involved in sustainable farming, fishing, logging or commerce. There was a hospital ship–the Columbia—that ran the coast and visited each port. People knew each other, welcomed voyagers, and shared food and news. A young woman, Betty Lowman Carey, upon completing her first year of university, paddled a dugout canoe she called Bijaboji, after her brothers Bill, Jack, Bob and Jimmy, from Puget Sound to Alaska during the summer of 1937. In her memoir, Bijaboji, she, too, recounted stopping off in many places where there were families and gangs of loggers or fishermen and women. The boat traffic up and down the coast seemed to be fairly regular, and included supply vessels, the hospital ship, and an American Scout training ship.

Even more recent accounts like Alexandra Morton and Billy Proctor’s book, Heart of the Raincoast and Proctor’s second book, co-authored with Yvonne Maximchuck, Full Moon, Flood Tide, about the Broughton of Billy’s childhood and young adulthood, both attest to a time when that part of the coast was far more active and inhabited than it is now.

Marike and Karin on Hakai Beach

This is also true of the place where we live in Nova Scotia, the Eastern Shore. It is also a place of First Nations middens, and white settler coastal communities once far more connected to distant places and much more populous than they are now. Before the highway went through in the 1960s, the Okay Steamship stopped in communities along the coast to take passengers, fish and provisions to and from Halifax. The islands in the Bay of Islands contain remains of little houses where the fishermen would stay once they rowed out to their grounds. A fishing smack would motor around pick up their catch each day and take it to the canneries or to a larger vessel to get it to market. Now those canneries and fish plants are all gone, the cod fishery is dead, and schools and churches and communities are shuttering, as their older inhabitants die, and the family houses tumble from their stony foundations.

We were very interested to find that Eric Peterson had been thinking about the Central Coast in ways that resonated with our own reflections on rural coastal Canada as we’ve encountered it on both east and west coasts. The work of the Hakai Beach Institute, its emphasis on how human and natural histories intertwine, fits right in with other research that we have been doing on the depopulation and corporate exploitation of marginal rural areas in this country.

Aggregating anenome eating a crab (and full of sand)

As we were ending our interview, a boat full of children from Bella Bella, supervised by a young woman who had taken the youth leadership course at Hakai, arrived for a day at the beach. We too were eager to return to the beach once we had fetched Elisabeth. At low tide we took a long walk to several other beaches connected by trails and boardwalks.

We had no trouble understanding why Hakai Beach and Pruth Bay in the Kwakshua Channel, is and has been for centuries, a sacred place.

Pruth Bay at night, looking out Kwakshua Channel to Fitz Hugh Sound

For more on the Hakai Beach Institute, see http://hakai.org/

48.683434

-123.405989